Phia Ménard

- workshop

Cifas explores gender identity. Phia Ménard will discuss transgender identity from artistic perspectives

In the mood for...?

"I was born with the feeling of being a stranger to my own body. As I was not born with the sex that matches my gender identity, I assume we all at some point question our own identity."

"In my (hormonal) transition from male to female body, it was not the physical changes which were the most significant - as I expected - but rather the invisible transformations which were the most impressive. My moods change, I could have never imagined how strongly."

"Do feminine and masculine moods exist? Are there common or separate moods? Social moods? Are these moods physiological? Are they walls of the intimate? These questions among many others, these experiences, I suggest to try them in a physical laboratory of our moods."

With the support of Halles de Schaerbeek

It is highly recommended that all participants of this workshop also register for the workshop given by Paul B. Preciado Biopolitical mutations and resistance. Body, Sex, Gender and Sexuality in the Pharmacopornographical Era.

Phia Ménard

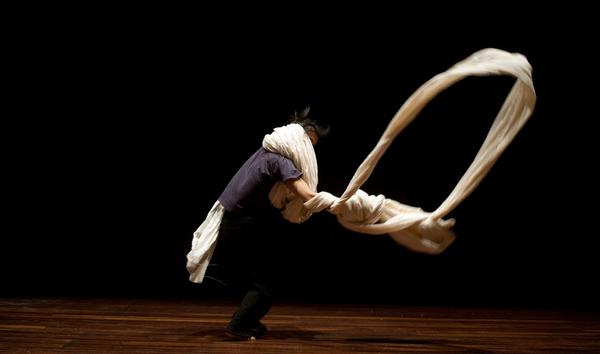

Previously juggler and performer for Jerome Thomas for many years, Phia Menard has developed since 1998 an unusual artistic universe that speaks of the world today and tackles a personal reflection on identity with the company Non Nova.

In Between, text by Ivan Kralj

“And the first came forth ruddy, all over like a hairy mantle; and they called his name Esau.” (Genesis 25:25)

Who could have imagined that the name for Female Esau, the lady with a beard, would be derived from the Bible, the sacred book whose laws are strictly based on “clear” gender – God made a man and a woman, nothing in between? Isaac’s hirsute son, described as unreligious and immoral, was the source of labeling many women who have, due to their excessive facial and body hair (usually linked to overproduction of androgen), become popular attractions of their time. The Hairy Maid, Barbara Urslerin from 17th century Bavaria was described by one doctor as a hybrid between a human woman and a male ape. In 19th century North Carolina a girl named Jane Barnell was sold to the circus because her mother thought her child’s deformity was caused by witchcraft. In 21st century New York, Jennifer Miller is proudly living her bearded lesbian identity, making a career both as a circus icon and a university teacher.

Throughout the centuries, ambiguities concerning gender expression have tickled human minds, emphasizing circus sideshow as a natural place of curiosity. The travelling community anchoring itself at the side of the grand show under the big top, made its business on displaying human oddities. The term exhibiting has fueled many debates on the ethics of such exposures, but at the same time, some of them, like bearded Annie Jones, have been earning higher salaries than the U.S. president. The sideshow offered a world of opportunities for those usually hidden from the world. The public was rushing to the creepy semi-scientific tent where historical terms of queer and freak met closely together, drawn by curiosity and - fear.

It is not odd when Phia Ménard in the 21st century after performing her contemporary circus show “P.P.P.” addresses the audience with a sentence: “Do not be afraid”. In the world of uniformity, fear is driving our attention when approaching the bearers of unclear gender labels. Fear and curiosity – they haven’t changed during the centuries. Ménard, a transgender artist on a real identity journey from Philippe to Phia, constructs the frightening threat from unknown Other through connecting her stage transition with almost half a tone of ice. The ice is melting. The artist is melting. What is the human state of matter?

In the wider context of performing arts, circus is a transgender art form itself, a form between genres. Always combining the elements from a very large diapason covering the joyful playground on one side and the critical political theatre on the other, the circus nurtured the hybridity, both in form and content, which has enabled the experience of an outcast to be familiar. Not here, not there, in between. Even today, when addressing the identity of contemporary circus, we can often hear an old question: “What is it?” (In 1860s, Barnum attached that question as an artistic name to a microchepalic boy, proclaiming him a missing link between humans and apes, according to then-new Darwin’s theory “Origin of Species”)

In order to address the common line of transgender and circus – the nonconventional identity – we have to go back to the freak show (Rachel Adams argues that freak, just like queer, is “a concept that refuses the logic of identity politics, and the irreconcilable problems of inclusion and exclusion that necessarily accompany identitarian categories”). Records tell us that one of the greatest freak show attractions would be a hermaphrodite or, as they called it, a half-and-half. Many of these were gaffed. In accordance to then popular belief that the right side of an individual is a strong, masculine side, and the left one the weak, feminine side, half-and-halves were double-sexed vertically. To emphasize the female side, the individual would fake a single, left breast (sometimes using dangerous injection of synthetic material) or endure heavy training to develop the muscularity of the right arm. It played with the idea of shock, not unknown to today’s sideshows. In Jim Rose Circus the transsexual porn star Buck Angel appears for the mere flesh exposure – a muscular security guard strips to reveal he has a vagina.

Gender identities have also been interchangeable – either through playing the identity (acrobat boys performing as girls answered the market’s need for female power), or playing WITH the identity (Ray Monde or Jean Cocteau4s favorite – Barbette were shifting gender during the act itself). Transformation between man and woman seemed amusing, sometimes confusing, always effortless. As Ménard reveals in “P.P.P.”, the real transition is a painful quest indeed, impregnated with the notion of risk, another element that transgender and circus share.

Ivan Kralj is an independent writer and a director of Festival novog cirkusa in Zagreb, Croatia (www.cirkus.hr).